TEIGNMOUTH POETRY FESTIVAL 2019 – COMPETITION RESULTS

OPEN COMPETITION

OPEN COMPETITION

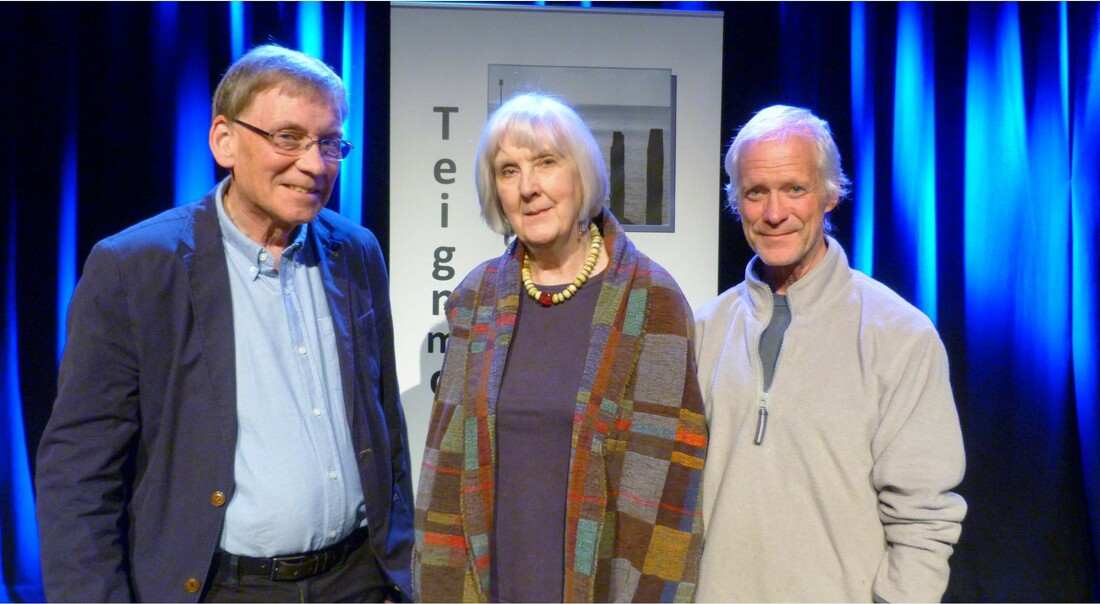

Photo - Viv Wilson

John Greening, (Judge) Linda Saunders and Scott Elder.

John Greening, (Judge) Linda Saunders and Scott Elder.

1st prize - Linda Saunders - Outside Chance

2nd prize - Tom Sastry - Cinderella and, by extension, all other stories

3rd prize - Scott Elder - Beyond the Tent

John Greening's adjudication report follows the winning poems.

The Winning Poems

1st Prize – Open Competition

Outside Chance by Linda Saunders

Baby wants new shoes, he’d say, to give a lift

to a small flutter each way on a horse

he’d wised up on in the racing columns.

But once he put all of five pounds to win –

and did – on an outsider, Burlington Arcade,

having dreamed himself among a wild crowd

yelling its name at the finishing line.

It was the sole evidence he could ever claim

for divine or psychic intervention

on behalf of any need of baby’s,

or his own. Just chance, he thought it, when a shell

slammed down beside him on the battlefield

and did not explode, while the world paused

as he said goodbye to it, aged seventeen –

he’d lied about his age to volunteer –

then found his glasses by another miracle,

and put them on to look into the future.

What is the difference between luck and grace?

His golfer’s swing was an action of honed

grace, preceded by a moment of stillness

something like prayer, club raised on high,

as if to align himself with every

quick nuance of this world’s here and there,

the sky’s depth, each inflected shadow, tilt

of wind and wish towards a promised land.

Among his silver trophies on the sideboard,

sharing the pride with ebony elephants

paraded trunk to tail, were the egg cups

awarded in those days for a hole-in-one.

A stroke of grace, I’d say, in league with luck

that the shell didn’t kill him, as was the perfect

loft and flight he gave a ball that landed

sweetly on the green and trickled home.

2nd Prize – Open Competition

Cinderella and, by extension, all other stories by Tom Sastry

Let her do it without a destiny.

Let her do it as the ugly sister.

Let her do it

because it is her fault

when she cannot point her body’s jumbled lines

at this dragon of a day.

Let her do it as the pumpkin squats,

smug as a moon on the step.

Let her

through a lifetime of midnights,

of enchantments collapsing on themselves,

do it

again and again.

Let her do it in memory

of love, or the hope of love.

Let her do it with a prince

who knows he is missing something about her

and cannot meet her eye.

Let her age.

Let her do it with bursitis and rheumatism.

Let her sweep it all up.

Then begin.

3rd Prize – Open Competition Beyond the Tent by Scott Elder

The circus is over

slipped from his grip

they carried her body

she flew to an end

beyond the tent

ten meters below

into a van

closing her circle

the cats will be shipped

within the circle

to a trace of jungle

defined by the tent

or piece of savannah

pitched one morning

I sip on whiskey

folded the next

slow as my gaze

sold for scrap

and focus my sights

for iron and brass

on Africa

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

ADJUDICATION BY JOHN GREENING, MARCH 23rd 2019

Just a few weeks before he arrived in Teignmouth in 1818, Keats famously wrote in a letter that ‘if poetry comes not as naturally as leaves to a tree, it had better not come at all’. Well, the poetic tree that I’ve been sitting under since the beginning of February had a lot of leaves. Over 800 in fact. However, unless you happen to be Keats, doing what comes naturally doesn’t always work, and a bit of cold-hearted redrafting might well have benefitted some of the entries I read through

To anyone who doesn’t spend a lot of time with poetry, it may seem impossible, even outrageous, to think that a judge can actually read 800 poems, let alone choose between them. But in the early stages it’s really no different from the chef who dips a finger in the sauce and knows immediately whether it’s any good. You wouldn’t expect much from a chef who’d never eaten well; who only knew English food of the 1950s, for example, or Victorian puddings. The same is true of poets who don’t read poetry.

What comes naturally as leaves to a tree may turn out to be several hundred leaves that are all alike. The judge of a poetry competition wants to be surprised, drawn in. And although it might be a story - or an emotion or an idea that does that,

most often in a good poem it will be the language itself. When Tom Stoppard was asked what Rosencrantz and Guildenstern was about, he said it’s about to make me rich. Bob Dylan had an equally witty reply. I think the best answer to the question, ‘what are your poems about’, is that they are about language.

*

Having begun with the 800, then, (canon to the left of me, canon to the right of me)

I fairly soon reduced the pile of entries to 150 or so that had some merit – here were poems that didn’t go for the easy phrase, the obvious metaphor, poems that made connections, that showed some appreciation of rhythm, word-music, aural effects,

some awareness of space and structure, of the extraordinary power locked in a line-break.

But I kept in mind that whatever a poem looks like on the page, however apparently elaborate the form, however much it displays the virtues of good prose, it shouldn’t sound like prose. If it sounds like prose, it probably is prose. (I won’t get into the vexed issue of the prose poem tonight – there were some. All I would say is that driving your car very fast on the airfield doesn’t turn it into a plane or you into a pilot.)

So, I have 150 poems which I need to read more closely, some of which I need to read aloud. Their subjects are various and sometimes unexpected – although some are more predictable: Grenfell Tower, climate change, the deaths of celebrities...

(not as much Brexit as I feared). There are – as always – many, many nature poems.

Oddly enough, in published volumes of contemporary verse, you won’t find a vast number of those. That’s probably because a nature poem is very difficult to do well. The temptation is to describe, to pile on the adjectives. Poetry is more about what appears when you start taking things away. Cut out everything you dare, as Basil Bunting said. See what you’re left with.

There was inevitably a lot of death. I have no problem with that – the elegy is among the most appealing genres in English poetry. But again it demands tact and judgment of tone. If you’re elegizing, it’s not a bad idea to have read Bishop King and Hardy, but also Douglas Dunn, Christopher Reid, Deryn Rees-Jones, Elaine Feinstein. There’s no point in writing poetry without reading the stuff.

Among the pieces that I enjoyed before the final sifting began, were poems about sardines, about shags, the Northern Lights, a Moorish palace, an old coat, a church door, Icarus, Edmund Burke, Olga Rudge, Georgia O’Keeffe, a mirror, a telescope, a beetle, Vietnam, knitting, how to recognise celebrated poets from the rear, greenhouses, geese, anger, grief, salt, the Titanic, the sea, the sea, the sea. And of course poetry itself. Perhaps all poems are to some degree about poetry itself.

Yet in the end what a poem is about is really not the point. Some of my favourite poems I have no idea what they are about.

*

My final list of ten fell into place fairly straightforwardly, and quite early on I sensed who was going to win.

Yet I went back several times to the best few dozen, changing my mind, but generally sticking with my first instinct - which was for those poems which avoid rhetoric, which work hard without necessarily showing it.

Sometimes it came down to just one false move, one smudgy line or misjudged word. If I couldn’t decide, then I went for the poem whose music most convinced me. There was some very fine writing and I wish I could have named a top twenty. That’s definitely the most painful part of the process, and I’d like to thank those who submitted: many more of you deserve prizes.

Of my top ten, I’ll say a brief word about each poem and we’ll hear some of the winners read. I’ll save the three prize-winners until last.

*

‘A Wooden Box’ by Howard Wright was a poem that grew on me and slipped into the top ten at the very last minute. It’s appealingly elusive and cinematically atmospheric. There’s a confident use of line-break, and a consistent tone. Keats would have admired what he called the capacity to be ‘in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason’.

‘Since Eels do not Keep Diaries’ by Mark Cooper feels as though it could be part of an eel sequence. It takes what is presumably a historical fact, a detail from the life of Freud, and describes it from the eel’s point of view. It’s a short poem, but nothing is off the peg, there are all kinds of felicities and arresting moments. An admirably clear style, too, and a terrific last line.

‘When the Music Stops’ by Gill Learner might well have been entered because its author knew I liked music. Well, I was certainly the right reader for its ingenious use of 24 titles from standard (and not so standard) classical repertoire from Vivaldi to Wagner to Dvorak to Britten to Messiaen to Adams. It even begins and ends with a famous Beethoven quotation. Caviare, perhaps, but delicious stuff. And very well judged with little musical flourishes in the writing.

‘Alone in Verona’ by Pamela Job is more densely written than some of my top choices. Kingsley Amis used to tut-tut about poems set in art galleries – but who cares any more when it’s this well done? In lovingly crafted quatrains, with a gentle guiding hand, and a convincing sense of when enough is enough, the poet quietly wins us over. It is formally very assured, and tells us interesting things, without becoming prosaic.

‘Cowslips’ by Stephen Fisher I liked a great deal even if I didn’t fully understand it – certainly there is much more in the poem than cowslips. It was one of the most ambitious pieces, pushing the language in challenging directions, toying in a fascinating way with teasing rhymes and rhythms. There is more than a touch of the Metaphysicals about it, George Herbert in particular, and something of Basil Bunting, Marianne Moore & Geoffrey Hill, too.

‘Thanks a lot, Shakespeare, for the Starling’ by Jonathan Greenhause shows just how much there is to be said for an inviting title – it certainly gives your poem a better chance in a competition. This felt a very American poem (the length of the title was one clue) and I responded to it at once: it’s not easy to balance formal assuredness with an anecdotal relaxed quality – moving perilously close to prose, but just sufficiently heightened. And it’s full of diverting material too.

‘Snow’ by Shae Spreafico was a surprise, a little gem that grew brighter each time I returned to it, so that it came to feel like something I already knew. It’s rare to find a modern short poem in rhymed quatrains that succeeds without sounding like Wordsworth, Housman or Emily Dickinson. They are certainly within earshot, but they would be impressed. The extended metaphor of conquest is wonderfully apt. And what a beautiful last line, in its sound, its immaculately judged weight, and its bold choice of ‘imperium’.

TOP THREE

In 3rd place, is ‘Beyond the Tent’ by Scott Elder. This is a fascinatingly laid out poem, a duologue, two voices singing together in the plainest of language – and here we do have a real sense of music in the words. The rhythms and aural interplay are much of what make the poem succeed, as well as those discreet internal rhymes (slipped/grip) and alliterations (piece/pitched, slow/sold/scrap). It’s a very good title too. It felt as if it might be part of a narrative sequence, a little drama even, but that doesn’t limit it. Nothing is overdone, nothing is obvious, but nor is it wilfully obscure. What we are given in fewer than 80 words tells an intriguing story, a very sad one if true. I kept asking myself, can so simple a poem really trump all those other filigree flights of intellect and poetic ambition? It does, because it achieves what it sets out to do, brilliantly and subtly.

In 2nd place we have another bold title, ‘Cinderella and, by extension, all other stories’ by Tom Sastry. This poem uses anaphora, the repetition of the same phrase, to provide its structure. That can be very dull if mishandled, but this is a free verse triumph. The lines are economical, varied, take unexpected directions – as in that superb withholding of ‘do it’ on its fifth appearance – and we’re kept on the edge of our seats as to what ‘it’ actually is. There’s wit, a strong sense of personal involvement, the poem’s images are always in sharp focus, and there are lovely musical touches such as the way ‘Let her age’ emerges climactically from ‘and cannot meet her eye’. There is no waste material here. The writer has learnt from poets as diverse as Ted Hughes and Penelope Shuttle how to do this kind of thing.

The winner of the Teignmouth Poetry Prize is ‘Outside Chance’ by Linda Saunders. This very fine poem is a portrait of a man (whom we may or may not be meant to recognise) evoked in simple formal tercets. As a piece of characterisation alone the poem is very strong, but it is the sustained tone (cool, thoughtful, ironic) that initially impressed me. It opens assertively and arrestingly – in fact, the first lines open up several possible directions in their tense and in the ambiguity of ‘give a lift’, which shifts across the line to a horse race, a dream, then a battlefield. The language is a successful blend of the colloquial and the heightened. There are touches of humour, hints of tragedy, all manner of intricacies. This poet knows what E.M.Forster meant by ‘only connect’, juxtaposing different elements with immense care and clarity: the shoes, the shell, the glasses, the egg-cups, the elephants, they all process and are processed into a dignified courtly music before our eyes – but the poet allows time for a big philosophical question too. I hope you will agree that ‘Outside Chance’ – which should perhaps be retitled ‘The Favourite’ – well deserves the top prize.